What Deep Brain Stimulation Actually Does for Parkinson’s

Deep Brain Stimulation, or DBS, doesn’t cure Parkinson’s. It doesn’t stop the disease from progressing. But for many people, it changes everything. If you’ve been on levodopa for years and now you’re stuck in a cycle of OFF periods - where movement freezes up - followed by sudden, uncontrollable twitching called dyskinesias, DBS can break that cycle. It works by sending tiny electrical pulses to specific areas of the brain that control movement. These pulses don’t kill brain cells or remove anything. They just reset the noisy signals causing tremors, stiffness, and slowness.

The procedure has been around since the late 1990s, but modern systems are smarter than ever. Today’s devices like Medtronic’s Percept™ PC and Boston Scientific’s Vercise™ Genus™ don’t just deliver constant stimulation. They can sense brain activity in real time. Some even adjust the pulse automatically when they detect abnormal patterns, like the high-beta wave bursts linked to Parkinson’s stiffness. This is called closed-loop DBS, and it’s already FDA-approved. It’s not science fiction - it’s happening right now in clinics across the U.S., Europe, and Australia.

Who Really Benefits from DBS?

Not everyone with Parkinson’s is a candidate. DBS works best for people with idiopathic Parkinson’s - the most common form - and only if their symptoms respond well to levodopa. That’s the golden rule. If your tremors or slowness improve dramatically after taking your morning pill, you’re likely a good fit. If you’ve tried multiple medications, still have severe shaking or freezing despite high doses, and your quality of life is slipping, DBS could be your next step.

But here’s what doesn’t work: DBS for atypical parkinsonism. If you have progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, or corticobasal degeneration, DBS won’t help. These conditions don’t respond to levodopa, and they won’t respond to brain stimulation either. Many patients are referred too late - after they’ve lost balance, speech, or memory. That’s when DBS loses its edge. The best outcomes come from people who are still physically active, mentally sharp, and have had Parkinson’s for at least five years.

The Three Big Criteria for Being a Candidate

Neurologists use a clear set of guidelines to decide who gets DBS. The first is levodopa response. You need to show at least a 30% improvement on the UPDRS-III motor test after taking your usual dose. This isn’t just a feeling - it’s measured in a clinic with timed tasks like finger taps, heel-to-toe walks, and standing from a chair.

The second is cognitive health. If your memory or thinking is already declining - say, your MoCA score is below 21 out of 30 - DBS can make it worse. You might develop trouble with planning, decision-making, or finding words. That’s not guaranteed, but it’s common enough that centers won’t operate unless you’ve passed neuropsychological testing. A 2022 study found 30% of patients reported post-op frustration not because of movement, but because they couldn’t manage their finances or follow recipes like before.

The third is disease duration. Most guidelines say five years minimum. Why? Because early Parkinson’s often responds well to meds alone. You need to have tried and failed enough combinations before jumping to surgery. The EARLYSTIM trial showed that even patients with just 4 years of disease who had disabling motor fluctuations still benefited significantly - but only if they met the other two criteria.

STN vs. GPi: Which Brain Target Is Right for You?

The two main targets for DBS electrodes are the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus interna (GPi). Both improve movement, but they have different trade-offs.

STN stimulation usually lets you cut your levodopa dose by 30-50%. That means fewer nausea episodes, less daytime sleepiness, and reduced dyskinesias. But it can also increase the risk of mood changes, depression, or speech problems. It’s the go-to for younger patients who want to reduce pill burden.

GPi stimulation doesn’t reduce medication as much, but it’s better at controlling dyskinesias directly. It’s often preferred for older patients or those already struggling with memory or depression. In the VA/NINDS CSP #468 trial, GPi led to 70% dyskinesia reduction versus 46% with STN. If your biggest problem is uncontrollable writhing after your pill kicks in, GPi might be the better choice.

Most centers now use bilateral implants - both sides of the brain - because Parkinson’s affects both sides of the body. But in rare cases, like someone with severe tremor on just one side, unilateral DBS can be enough.

What the Surgery Actually Involves

DBS isn’t open-brain surgery. You’re awake during most of it. A metal frame is attached to your head, and high-resolution 3T MRI scans guide the team to the exact spot in your brain. Then, using microelectrodes, surgeons listen to individual brain cells firing. They’re looking for the telltale patterns that signal the STN or GPi. When they find it, they test stimulation - asking you to move your hand, speak, or walk - while watching for improvement and side effects.

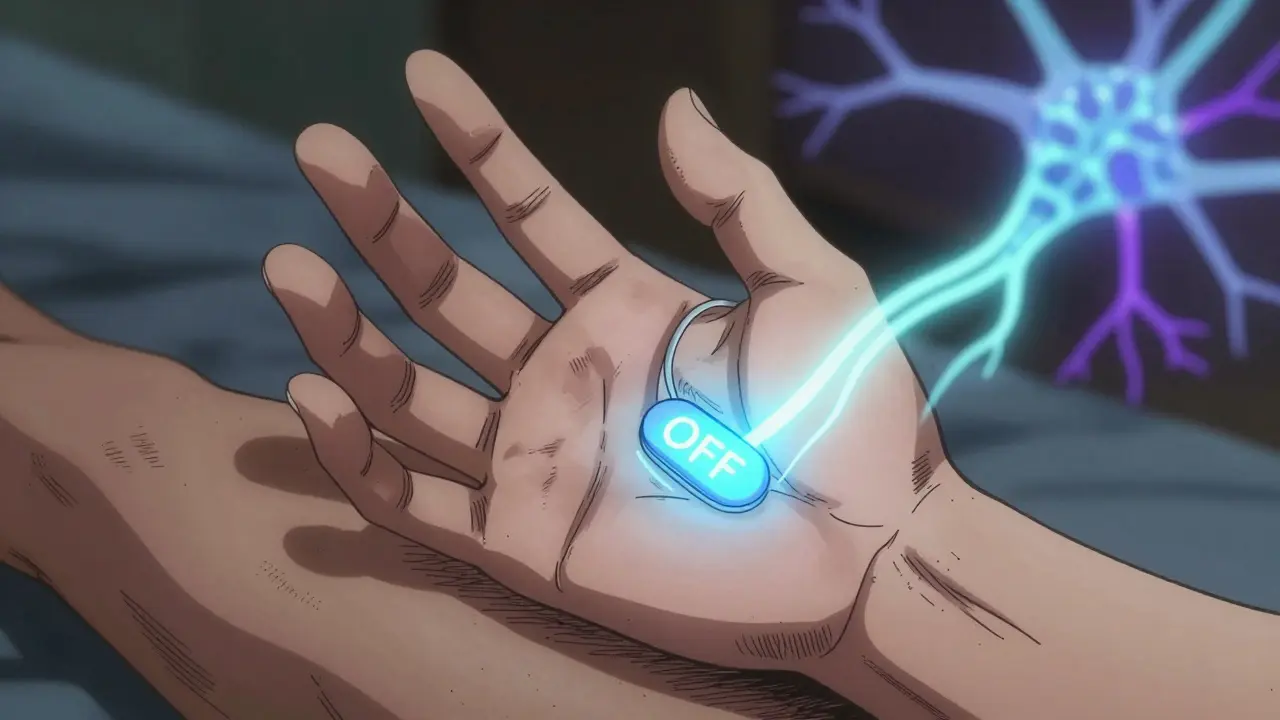

The whole thing takes 3 to 6 hours. You might feel a tingling or warmth during testing, but no pain. After the electrodes are placed, wires are threaded under your skin to a battery pack implanted near your collarbone or abdomen. That’s the IPG - the implantable pulse generator. It’s about the size of a stopwatch. You’ll go home in 1-2 days.

It’s not a quick fix. The device is turned on about 2-4 weeks after surgery. Then comes the long phase: programming. It takes 6 to 12 months to fine-tune the settings. You’ll need monthly visits at first. Each tweak can take an hour. You’ll be asked to keep a symptom diary: when you feel stiff, when you twitch, what meds you took, and how the stimulation felt. This is critical. The right settings can make you feel like you did 10 years ago. The wrong ones can make you worse.

Costs, Risks, and What Insurance Covers

DBS isn’t cheap. In the U.S., the total cost - surgery, device, hospital stay, follow-ups - runs between $50,000 and $100,000. Medicare and most private insurers cover it for Parkinson’s, but getting approval can take 3-6 months. You’ll need documentation showing you’ve tried at least three different meds and still have disabling symptoms.

Hardware complications happen in 5-15% of cases. Wires can break, leads can shift, infections can develop around the battery. About 1 in 100 people have a brain bleed during surgery - serious, but rare. Most people don’t need revision surgery, but if your battery runs out (non-rechargeable ones last 3-5 years), you’ll need another operation to replace it. Rechargeable models last 9-15 years but require daily charging, which some patients find burdensome.

There’s also the hidden cost: time. You’ll need to miss work, drive long distances for programming, and manage a new routine. Many patients say the hardest part isn’t the surgery - it’s waiting for results and learning how to live with a device that needs constant attention.

What Patients Really Say - The Good, the Bad, and the Unspoken

On Parkinson’s forums, the stories are raw. One man in Ohio said DBS cut his OFF time from six hours a day to under an hour. He could hug his grandkids again. Another woman in Canada said her tremors vanished - but she lost her ability to plan her week. “I used to be the one who organized family trips,” she wrote. “Now I forget what day it is.”

Many expect DBS to fix everything: speech, balance, memory, mood. It won’t. Gait freezing and postural instability improve by only 20-30%. Depression and anxiety often persist. One Reddit user summed it up: “I thought DBS would make me normal again. It made me better - but not normal.”

Still, 70-80% of properly selected patients report major quality-of-life gains. The EARLYSTIM trial showed a 23-point improvement on the PDQ-39 quality-of-life scale - more than double what medication alone achieved. For many, it’s the difference between staying home and going out. Between needing help to dress and doing it alone.

Why So Few People Get It - And How to Avoid Being One of Them

Only 1-5% of eligible Parkinson’s patients get DBS. Why? Because most neurologists don’t bring it up. Or they wait too long. The Parkinson’s Foundation calls it a “markedly underutilized” treatment. Patients often hear about it from other patients, not their doctors.

If you think you might be a candidate, don’t wait for your neurologist to mention it. Ask. Say: “I’m having trouble with OFF periods and dyskinesias despite my meds. Is DBS something I should be evaluated for?” Then push for a referral to a movement disorders specialist - not just any neurologist. Look for a center that does at least 50 DBS procedures a year. Higher volume means fewer complications.

Get a neuropsychological evaluation before you even think about surgery. Don’t skip the MRI. Don’t assume you’re too old. Age isn’t the barrier - brain health and levodopa response are.

What’s Next for DBS?

The future is personalized. New research is looking at genetic markers - like the LRRK2 mutation - to predict who responds best. Some centers are testing DBS in patients with just three years of Parkinson’s. Closed-loop systems are getting smarter, learning your patterns and adjusting without you lifting a finger. There’s even early work on using DBS for depression and sleep issues in Parkinson’s - not just movement.

But for now, the best tool we have is still the one we’ve had for decades: careful selection. Know your symptoms. Know your meds. Know your limits. And if you’re struggling, ask for help - not just for your body, but for your future.

8 Comments

Marian Gilan

January 27, 2026 AT 03:12so i heard dbs is just a cover for the government to implant tracking chips in your brain... they said it's for parkinson's but my cousin's neighbor's dog started talking in binary after his surgery. 🤔

Conor Murphy

January 28, 2026 AT 20:09this is actually one of the most clear explanations i've read. my dad had dbs last year and it gave him back his mornings - he can now make coffee without dropping the pot. ❤️

Conor Flannelly

January 30, 2026 AT 04:07what strikes me most isn't the tech - it's how we've normalized brain surgery as a lifestyle upgrade. we don't fix the environment, we don't fix the meds, we just poke holes in the skull and call it progress. it's like patching a sinking ship with duct tape and hope. still... if it lets someone hold their grandkid without shaking? i won't judge.

Patrick Merrell

January 30, 2026 AT 17:03if you're dumb enough to let a machine control your brain then you deserve what you get. people used to live with tremors and still raised kids and built businesses. now we're all just waiting for a battery to die so we can blame someone else. #weak

shivam utkresth

February 1, 2026 AT 05:46yo from india here - we got dbs in mumbai and bangalore but it's like 3x more expensive than meds. my uncle had it done and the docs said he was a perfect candidate: levodopa worked, no dementia, 7 years in. now he’s got this weird habit of adjusting his implant with a magnet like it’s a remote control. we all laugh but honestly? he’s back to gardening. that’s worth every rupee.

John Wippler

February 2, 2026 AT 03:13i used to think dbs was sci-fi until my sister got it. she went from barely walking to hiking trails in 6 months. the programming phase? brutal. she cried through 3 sessions. but now? she dances with her husband again. not perfect. not cured. but alive. that’s the win. don’t wait for the perfect moment - the perfect moment is when you still have the will to fight.

Joanna Domżalska

February 3, 2026 AT 01:2170-80% improvement? sure. but what about the 20% who turn into emotional zombies? my aunt got dbs and now she forgets her own birthday. they say it's 'cognitive trade-off' like it's a coupon. no. it's losing pieces of yourself for a few less tremors. this isn't progress. it's a gamble with your soul.

Josh josh

February 3, 2026 AT 16:24dbs saved my life no cap. 5 years of being a ghost now i can hold my coffee without spilling it. the battery died last year had to get a new one but worth it. just ask your doc dont wait