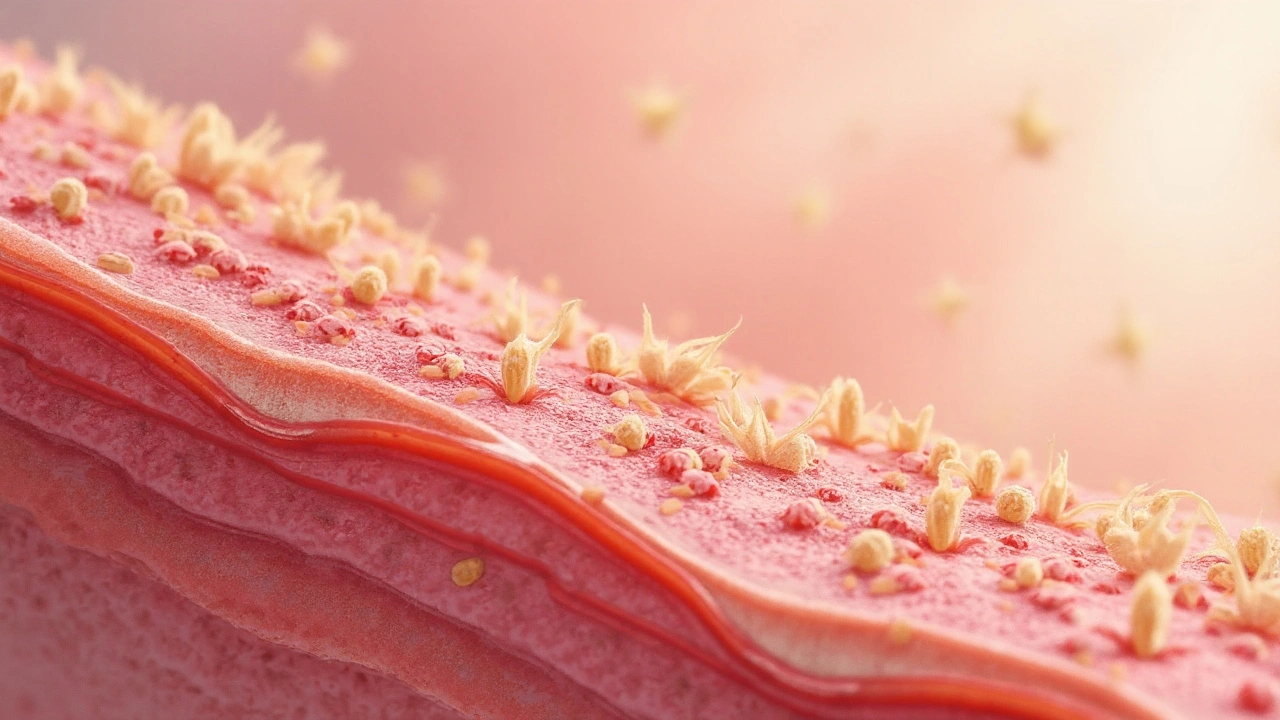

Skin parasites is a group of organisms that live in or lay eggs within human skin. They range from microscopic mites to tiny fly larvae, and each follows a distinct life‑cycle that can cause itching, rashes, or even severe tissue damage. This guide breaks down the most common culprits, how to recognize an infestation, and what steps you can take to clear and prevent them.

Why Skin Parasites Matter

When an organism burrows into the epidermis or deposits eggs just beneath the surface, the immune system reacts with inflammation, itching, and sometimes secondary infections. Untreated cases can lead to chronic skin conditions, scarring, or systemic complications, especially in immunocompromised individuals. Understanding the biology behind each parasite helps you act fast and choose the right treatment.

Common Culprits That Live or Lay Eggs in Your Skin

Below are the six parasites you’re most likely to encounter in everyday life. Each entry includes the scientific name, how you get infected, typical skin lesions, and first‑line therapy.

| Parasite | Scientific Name | Transmission | Typical Lesion | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scabies mite | Sarcoptes scabiei | Prolonged skin‑to‑skin contact | Intense itching, burrow lines 2-10mm long | Permethrin 5% cream for 8h, repeat in 1week |

| Demodex | Demodex folliculorum / D. brevis | Normal part of skin flora; over‑growth linked to oily skin | Rosy papules, folliculitis, itching around eyelids | Tea‑tree oil washes, ivermectin oral dose |

| Cutaneous larva migrans | Ancylostoma braziliense (hookworm) | Contact with contaminated sand or soil | Serpiginous, creeping rash that advances 1-2mm/h | Ivermectin single dose or albendazole 400mg daily for 3days |

| Tungiasis | Tunga penetrans | Walking barefoot on sandy, dusty ground | Red, painful nodule with a central black dot (the flea’s abdomen) | Extraction of flea, topical ivermectin, wound care |

| Botfly myiasis | Dermatobia hominis | Egg‑laden flies deposit larvae on clothing; they penetrate skin | Fleshy, ‘boil‑like’ nodule with a central breathing pore | Surgical removal, occlusion with petroleum jelly, antibiotics if infected |

| Fly larval myiasis | Cochliomyia hominivorax (New World screwworm) | Open wounds or ulcers contaminated with fly eggs | Rapidly expanding, foul‑smelling ulcer with maggots | Ivermectin, thorough debridement, wound dressings |

How These Parasites Live or Lay Eggs in the Skin

Even though they belong to different taxonomic groups-mites (Arthropoda), nematodes (roundworms), and flies (Diptera)-their strategies converge on one goal: a protected environment and a steady food supply.

- Burrowing and feeding: The scabies mite tunnels just beneath the stratum corneum, where it feeds on skin cells and lays eggs in the same passage.

- Follicular colonisation: Demodex lives inside hair follicles and sebaceous glands, laying eggs that hatch in situ; an over‑abundance can clog pores and trigger rosacea‑like flare‑ups.

- Surface migration: Hookworm larvae of cutaneous larva migrans wander across the epidermis, releasing enzymes that dissolve tissue as they move, creating a visible, snake‑like track.

- Embedded flea abdomen: Female tungiasis fleas actually enlarge inside the epidermis, swelling up to 1cm and producing thousands of eggs that eventually drop onto the ground.

- Larval breathing pores: Botfly larvae keep a tiny opening to the outside for oxygen; they grow as the host’s immune response forms a capsule around them.

- Massive tissue consumption: Screwworm larvae feed on living tissue, creating a cavity that serves as both a home and a buffet.

In each case, the parasite’s life‑cycle stage inside the skin triggers an inflammatory response that explains the itching, pain, or visible tracks.

Spotting the Signs: Symptoms and Physical Clues

Early detection is key. Below are the hallmark clues for each parasite, grouped by visual pattern.

- Burrow lines (2-10mm): Classic for scabies; often found between fingers, wrists, or around the waist.

- Fine papules around eyelids or cheeks: Suggest Demodex over‑growth; may be accompanied by dry eye symptoms.

- Serpentine, erythematous tracks: Pathognomonic for cutaneous larva migrans; the line advances a few millimetres each hour.

- Red nodule with central punctum: Indicates tungiasis; the punctum is the flea’s breathing hole.

- Boil‑like nodule with a central pore: Botfly myiasis; the pore may exude serous fluid.

- Foul‑smelling, expanding ulcer containing visible maggots: Screwworm myiasis; rapid tissue loss is a red flag.

Accompanying symptoms often include intense itching, secondary bacterial infection, and in severe cases, fever or lymphadenopathy.

Getting the Right Diagnosis

Because many skin eruptions look alike, a clear history and visual exam are essential. Dermatologists may use:

- Dermatoscopy: Spotting the tiny entry point of a flea or the regular pattern of scabies burrows.

- Skin scraping: Microscopic identification of mites or Demodex.

- Skin biopsy: Needed for atypical myiasis or when secondary infection obscures the lesion.

- Serology or PCR: Rarely, for systemic parasitic infections that also affect the skin (e.g., onchocerciasis).

In most routine cases, a visual diagnosis is sufficient and allows same‑day treatment.

Treatment Options: What Works and What Doesn’t

Effective therapy hinges on targeting the specific organism while minimizing skin damage.

| Parasite | Drug/Procedure | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Scabies mite | Permethrin 5% cream | Apply 8h, repeat in 7days |

| Demodex | Ivermectin oral 200µg/kg | Single dose, repeat after 2weeks if needed |

| Cutaneous larva migrans | Ivermectin 200µg/kg | Single dose, or albendazole 400mg ×3days |

| Tungiasis | Manual extraction + topical ivermectin 1% | Single session; wound care 5‑7days |

| Botfly myiasis | Surgical removal or occlusion (petroleum jelly) | One‑time procedure |

| Screwworm myiasis | Ivermectin 200µg/kg + debridement | Repeat daily until larvae gone |

Topical steroids may relieve itching but never replace antiparasitic drugs. Over‑the‑counter antihistamines help with sleep, but the parasite must be eradicated to stop the cycle.

Prevention: Keeping Parasites Out of Your Skin

Most skin parasite infections are avoidable with simple hygiene and environmental steps.

- Wear shoes on beaches and in rural areas: Stops tungiasis and hookworm larvae from penetrating soles.

- Wash hands frequently and avoid sharing clothing or bedding: Reduces scabies transmission.

- Maintain facial cleanliness, especially for oily skin types: Limits Demodex over‑growth.

- Inspect clothing and sleeping areas when traveling to tropical regions: Botfly eggs may be stuck to fabric.

- Prompt wound care: Keeps flies from laying eggs in open lesions.

For travelers, a single dose of ivermectin before a beach vacation can provide a safety net against hookworm skin larvae, according to a 2023 field study in Southeast Asia.

Related Topics You Might Explore Next

If you found this guide useful, consider diving deeper into:

- Systemic parasitic infections that manifest on the skin (e.g., leishmaniasis).

- Advanced dermatoscopic techniques for differentiating mite burrows.

- Public‑health strategies for endemic tungiasis in sub‑Saharan Africa.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get scabies from a pet?

No. The scabies mite that infests humans (Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis) is species‑specific. Pets can carry a similar mite, but it does not reproduce on human skin.

Why does my skin itch more at night when I have mites?

Mite activity peaks in the evening, and the skin’s temperature drops, which heightens nerve sensitivity. The combination makes the itching feel worse at night.

Are over‑the‑counter anti‑itch creams enough for cutaneous larva migrans?

They may calm the itch, but they won’t kill the migrating larvae. Prescription antiparasitics such as ivermectin or albendazole are required for cure.

How do I safely remove a tungiasis flea without spreading eggs?

Use a sterile needle or tweezers to gently extract the flea’s abdomen, then apply topical ivermectin to kill any remaining eggs. Avoid squeezing the flea, which could release eggs into surrounding skin.

Is myiasis a sign of poor hygiene?

Not always. While open wounds provide a breeding ground, myiasis can also occur after trauma or surgery in otherwise healthy individuals, especially in warm climates where flies thrive.

Can Demodex cause permanent skin damage?

When over‑growth leads to chronic inflammation, it can cause scarring or pigment changes, particularly around the eyes. Early treatment usually prevents lasting effects.

13 Comments

Mike Laska

September 22, 2025 AT 13:14This is the most terrifying thing I’ve read all year. I just got back from a beach trip and now I’m staring at my feet like they’re alien landscapes. That tungiasis flea thing? I’m never walking barefoot again. Never.

Also, why does no one talk about how botflies are basically sci-fi horror movies in real life? They’re not parasites-they’re body snatchers.

Andy Ruff

September 23, 2025 AT 13:12People still don’t understand that this isn’t ‘bad hygiene’-it’s a failure of public health infrastructure. You think I want to crawl around in dirt with my bare feet? No. I want clean roads, proper waste disposal, and fly control programs. But no, we blame the victim instead of fixing the system.

And don’t even get me started on how we ignore tropical diseases until they show up in our own backyards. Then suddenly everyone’s an expert. Pathetic.

Hazel Wolstenholme

September 23, 2025 AT 14:24While the article is technically accurate, it lacks nuance in its taxonomic framing. The notion that mites, nematodes, and diptera ‘converge’ on a singular strategy is a gross oversimplification rooted in anthropocentric reductionism.

Scabies mites don’t merely ‘burrow’-they engage in a complex, co-evolved epidermal niche construction. Demodex isn’t an ‘overgrowth’-it’s a dysbiosis of the pilosebaceous unit, analogous to gut microbiome collapse. And calling tungiasis a ‘flea’? Taxonomically inaccurate-it’s a Siphonapteran, not a true flea. The taxonomy matters. The language matters.

Also, why is ivermectin listed as first-line for botfly? Surgical extraction is the gold standard. The petroleum jelly method is a folk remedy with anecdotal support, not evidence-based practice. This article reads like a Wikipedia edit by someone who watched three YouTube videos.

And where’s the discussion of resistance patterns? The rise of permethrin-resistant scabies strains in Australia and Southeast Asia is well-documented. Ignoring it is irresponsible.

Matthew Kwiecinski

September 23, 2025 AT 19:36Demodex is not a parasite. It’s a commensal. You only get symptoms when your immune system is broken or you’re using too much retinoid cream. The whole ‘overgrowth’ narrative is marketing nonsense pushed by skincare companies selling tea tree oil. I’ve had Demodex my whole life. No issues. No treatment needed.

Also, permethrin for scabies? That’s outdated. Ivermectin is better. And cheaper. And doesn’t require you to sit in a tub of cream for eight hours like a weirdo.

Pradeep Kumar

September 24, 2025 AT 00:50As someone from rural India, I’ve seen tungiasis up close. It’s not just about shoes-it’s about poverty, lack of clean water, and no access to clinics. One woman I knew had 17 fleas embedded in her foot. She couldn’t walk for months. No one helped her until a mobile health team came through.

Education matters. But so does compassion. These aren’t ‘cases’-they’re people. Let’s not reduce their pain to a textbook diagram.

Also, ivermectin is available for free in many Indian public hospitals. If you’re reading this and have access to healthcare-don’t wait. Get checked if you have weird rashes. Early = easy.

Eileen Choudhury

September 25, 2025 AT 02:52Okay but imagine if we treated our skin like a garden instead of a battlefield. Demodex? Maybe it’s just trying to survive. Scabies? Maybe your skin’s crying for balance. I’ve stopped using harsh chemicals and started with coconut oil, probiotic cleansers, and grounding myself barefoot on grass. My skin hasn’t been this calm in years.

Not saying ditch the meds-just say hi to your skin first. It’s been through a lot.

Also, botfly larvae? They’re fascinating. Nature’s little architects. We should respect the process, even if it’s gross. 🌿✨

Alexa Apeli

September 26, 2025 AT 12:45Thank you for this meticulously researched and profoundly important guide. The clarity with which you’ve presented complex parasitological concepts is both admirable and deeply reassuring.

I especially appreciate the inclusion of diagnostic methods such as dermoscopy and skin scraping-these are indispensable tools in clinical dermatology. Your emphasis on early intervention and preventive measures reflects a holistic, patient-centered ethos that is all too rare in medical communication today.

May this article reach every traveler, parent, and healthcare provider who needs it. With gratitude, and a renewed commitment to skin health, I remain,

Yours in wellness,

Alexa Apeli, MD (Hon.)

Keerthi Kumar

September 28, 2025 AT 07:43There’s a cultural silence around these things. In many parts of South Asia, people are ashamed to say they have ‘bugs under their skin.’ They suffer in silence. They use home remedies-neem paste, turmeric, kerosene. Some get better. Some don’t.

We need community health workers who speak local languages. We need posters in village clinics. We need to stop making this a medical secret.

And for the love of God, stop blaming people for walking barefoot. The soil isn’t the enemy. The lack of sanitation infrastructure is.

Let’s talk. Let’s listen. Let’s act. 🌏❤️

S Love

September 29, 2025 AT 16:29Minor correction: The scientific name for the New World screwworm is Cochliomyia hominivorax, not Cochliomyia hominivorax. Spelling matters. Also, the treatment for cutaneous larva migrans is albendazole 400 mg daily for three days, not ‘400mg ×3days’-proper units and spacing are essential in medical writing.

Otherwise, excellent summary. Clear, accurate, and actionable. Well done.

andrea navio quiros

October 1, 2025 AT 07:04we think skin is ours but it’s not really it’s a shared ecosystem like a forest and we just got here first

mites were here before us they’ll be here after us

we call them parasites because we’re scared of what we don’t understand

maybe the itching isn’t a problem maybe it’s a message

our bodies are trying to tell us something

we fix the symptom not the cause

we use chemicals not curiosity

we fear the small things

but the small things know the most

Pritesh Mehta

October 1, 2025 AT 15:10Western medicine treats these as ‘rare’ conditions because they don’t affect rich white people. But in India, Africa, Latin America-this is daily reality. We don’t have the luxury of ‘wait and see.’ We treat it on the spot or we lose limbs.

And yet, you get some guy in a hoodie in Oregon telling you tea tree oil is ‘holistic’ and that’s better than ivermectin. Please. We’ve been treating this for centuries with methods that work. You’re not ‘alternative’-you’re dangerously uninformed.

Stop romanticizing suffering. Stop calling it ‘nature’s balance.’ My cousin had a botfly larva crawl out of his ear. That’s not ‘fascinating.’ That’s trauma.

Stop pretending you know what it’s like to live without a clinic five miles away.

Melissa Kummer

October 2, 2025 AT 20:23This is exactly the kind of information every parent, traveler, and outdoor enthusiast needs. I’ve printed this out and put it in my first-aid kit. Thank you for the clarity, the organization, and the emphasis on prevention.

Especially the part about inspecting clothing before traveling-my sister didn’t know botfly eggs could hitch a ride on jeans. She’s now a convert.

Let’s spread this far and wide. Knowledge is the best defense.

With sincere appreciation,

Melissa Kummer, RN

Zachary Sargent

October 3, 2025 AT 11:51So I just got back from Thailand and I’ve got this weird red line on my foot that moves. I’m 90% sure it’s hookworm. I’m not telling my mom. She’ll have a heart attack.

Also, if you’re reading this and you think you have one of these things-just go to a dermatologist. Don’t YouTube it. Don’t Google it. Don’t ask Reddit. Go. Now.

And for the love of god, wear shoes.